At that point, what did you know about reggae?

I heard Bob Marley for the first time while he was with the Wailers in 1974, totally by fluke. Eugenie and I were on our way to Minnesota and we stopped for a few days to see a friend in Chicago. One night she said, “Let’s go to a club with interesting music,” and it was Bob Marley. It was an unbelievable gig.

What sort of music were you into back then?

Many things. Mainly rock music and R&B. My wife had two brothers who played the guitar. And lots of blues, of course. If my heart had only room for one kind of music, it would have to be the blues. Everything began in a bizarre sort of way through my love for rebetika.

Rebetika being a Greek form of the blues.

What happened with rebetika and the blues happened with Bob Marley’s music as well. Rocksteady and ska were already around, but when I heard Augustus Pablo I realized that it was something very profound, something over and above what you heard. Reggae had musical depth and a great variety of sounds. If you look at reggae between the end of the 60s and the beginning of the 70s, you won’t believe that it was all done by the same 20-odd people in the Kingston studios. Literally. All these genres emerged simultaneously and from the same musicians—ska, rocksteady, reggae, rocker, the dubs.

They were one and the same?

The people who began ska also began reggae: no more than two or three drummers, guitarists, and bassists. The quality of the singers became crucial, their ability to inspire the musicians. The sound was there, and the only thing missing were the little 45 rpms that had to be cut as quickly as possible—in two hours, even in a half hour—so that costs were kept at a minimum. The recordings would be done in rudimentary studios, the new tracks played in big outdoor dance sessions, over the weekends, traveling with vans chock-full of amps and massive speakers. This was music intended for immediate consumption. Later they began recording 45s on the spot and selling them in just a few shacks or shops. That’s how it was. And they sold more in the UK and fewer in the US.

The UK was always more open to reggae.

Yes, the fact that Jamaica was a British colony was a factor in this. It was easier for a Jamaican to go to England than to the US, because of passport and green-card issues. Also, they had absorbed reggae to a greater degree. Bands such as 2 Tone, the Selecter, and others were all very important. I also believe that punk music owes a lot to reggae. They had the same attitude. This was also the reason there were punk covers of reggae tracks.

Was all this a strictly local Jamaican scene? Was it some sort of ghetto?

Very localized. You could call it a ghetto, but it wasn’t really. Ghettos in Jamaica were neighborhoods of blocks built around courtyards, like Athens in the 20s and 30s or like African villages. In them were social structures with a life of their own that functioned separately from the broader context, which was the government, the police, the army, and the justice system. The local radio stations seldom played any reggae. They played soul and disco, as did the clubs.

They didn’t support their own scene?

It wasn’t their own scene, because no one made any money from it. Only a few guys who owned the sound systems made any money. In fact, only two people were behind most of the first releases: Coxton Dodd [of the Studio One label] and Duke Reid [of the Treasure Isle label]. When the genre started gaining ground internationally, things began to change, and by the mid-70s reggae as we knew it disappeared. It was impossible for the same people to be in so many bands. There were only enough musicians for five or six bands. Bob Marley took with him some of the best. The others started moving to New York and London. By the end of the 70s, there was no one left. You could say that it all ended with the One Love Peace Concert in 1978.

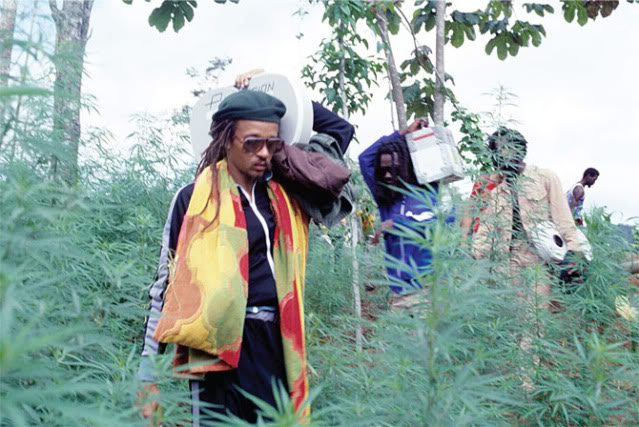

It’s interesting that Rockers is missing many of the typical Jamaican ingredients, such as the palm trees and the beaches. Why is that?

It’s done on purpose. My aim in the film was very simple: From the beginning I thought of it as a song, and so the issue was not what to include, but what I would leave out. I had to choose. You can’t fit everything in a film. My grandmother, who had never gone to school and was a wonderful woman, would watch me draw when I was young and say, “This is too loaded,” if I had put in too many elements. In my case, I tried to stay within a certain framework and I did not see myself as a filmmaker, but generally as an artist.

Were you confident your movie would be a success?

I felt that the film was going to be exceptional, but at the same time my mind was fixed on completing it. Anything could happen during the shoot, which could make the whole project go up in flames. One day a kid could pull the trigger and kill someone—this is Kingston we are talking about, a place were 600 kids were killed during that year—and this would be a total disaster. That would be the end. A great part of the population got killed, and most of the time for no reason.

Over what, exactly?

This was gang warfare, but believe it or not the law did not discourage this because guns were everywhere. There was a lust for guns, it was very cool to carry one, and there were also politicians who went around with entire armies of armed guys. The greatest fear was these 11- and 12-year-old kids—you could not tell what they would do next, and they could kill just like that. I think I was very lucky to have completed this film. Every day I lived in fear that someone from the crew or an actor would get killed.

Would you say the scene resembles contemporary hip-hop?

Not really, because the people who lived there and made music were scared stiff of guns. They did not use any themselves. They weren’t idiots, you know. They suffered from guns. What makes me view Bob Marley as a hero is that he came back and tried to help establish some order. Of course, he couldn’t do this across the board, and there were many reactions from people in the street. But this effort to bring about a truce and peace stopped the violence for a year. Then it began once again, and before the end of the year both gang leaders were dead. Then cocaine entered the picture.

Did it replace marijuana?

Weed was still there, but it was the cocaine that killed and devastated. There was lots of money involved; people became aggressive and started killing each other. But you could also meet the sweetest and most interesting people—a factory of expressions crammed into such a small place. I am not talking about Kingston. The small, scanty houses built in clusters were more like favelas and less like ghettos. It is in these few places here and there that all the Rasta musicians lived.

Who exactly are the Rasta?

Reggae and Rasta go together, they became a single thing. They became the reason every young guy in Kingston could say, “Yes, now I have a flag, I have a nation, a God, and now fuck you, white guy. And you too, baldy.” Marcus Garvey was a key figure in all this. Garvey tried to organize black people and to persuade them to return to Africa. “The black man is not a white man, the black man belongs in Africa.”

So racism was prevalent.

Definitely. They would say to me, “Greek man, we don’t want anything from you because anything you give us is not yours to give. This is my own life, and my own life is black and can never improve with your care. I want to take care of my life, to control it, and so I will go to Africa, which is full of black people, and I will be part of this other world, of this black life.” There was racism even between them, between people with darker skin and those with lighter skin, between the educated and the uneducated.